Table of Contents

Picture a Sumerian farmer watching a shadow creep across a stick to decide when to irrigate — and you checking your inbox before breakfast. Different centuries, same impulse: do more with what you have.

While it’s easy to think of productivity as a consequence of the modern age, it’s actually been a human concept for millennia.

But it got us thinking: has it always been as intense as it is today? What brought us to an era of productivity that has most people feeling like failures?

Let’s trace the history of productivity, not as a list of inventions, but as a shifting idea: from survival in ancient fields to speed in factories to thinking work on laptops.

What Does “Productivity” Really Mean?

At its core, productivity is output divided by input. In short, how much value you create for the time and energy you spend.

Economists often use labor productivity (GDP per hour worked) to compare nations; it’s a clean way to see whether an economy turns effort into results. But that number hides messy realities: people, tools, attention, and health.

In your day-to-day, think in ratios: What am I getting for each hour of focused effort? That framing works whether you write code, run a clinic, or lead a class.

It also explains why changing your measurement system (fewer context switches, better tools, clearer priorities) can beat trying to “work harder.”

We’ve got a whole guide on this topic: Productivity: Explain Like I’m 5! – in case you find the jargon-filled economics definitions a little difficult to follow.

Ancient Blueprints of Productivity: From Calendars to Culture

Before the steam engine or the spreadsheet, productivity was about making survival more reliable.

Ancient societies created both practical systems — tools to manage time, trade, and labor — and philosophical systems — cultural values that shaped how people thought about effort.

Together, they formed the earliest blueprints for how humans “get more done.”

Practical Systems: Tools, Calendars, and Ledgers

The first leaps in productivity were about turning chaos into coordination.

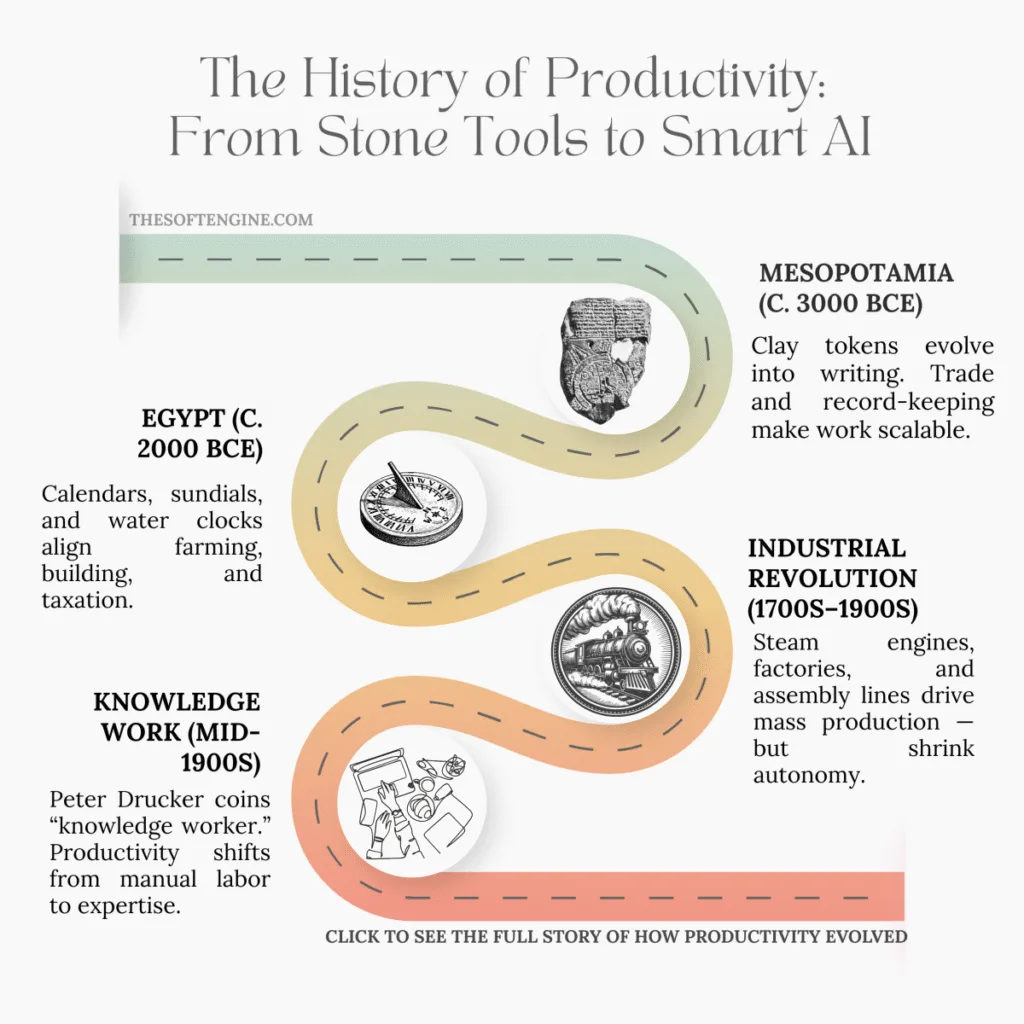

- Mesopotamia (c. 3000 BCE): Clay tokens were used to track goods, which evolved into cuneiform writing. This shift allowed merchants to manage trade at scale — not by memory, but by permanent, verifiable records. That simple act of accounting multiplied trust and efficiency.

- Egypt: The 365-day solar calendar, along with sundials and water clocks, gave farmers and builders the ability to synchronize with natural cycles. Planting and harvesting could be planned more precisely, and taxation became systematized. In essence, timekeeping turned agriculture and governance into predictable projects.

- China: Early dynasties developed advanced bureaucratic record-keeping systems to administer vast populations, supported by innovations like standardized coinage and, later, the abacus. Productivity here meant scaling administration without collapse.

These tools weren’t “apps,” but they served the same purpose: reducing friction and uncertainty so more work could be done with less waste. They would set the foundation for the future.

Philosophical Systems: Cultural Values Around Work

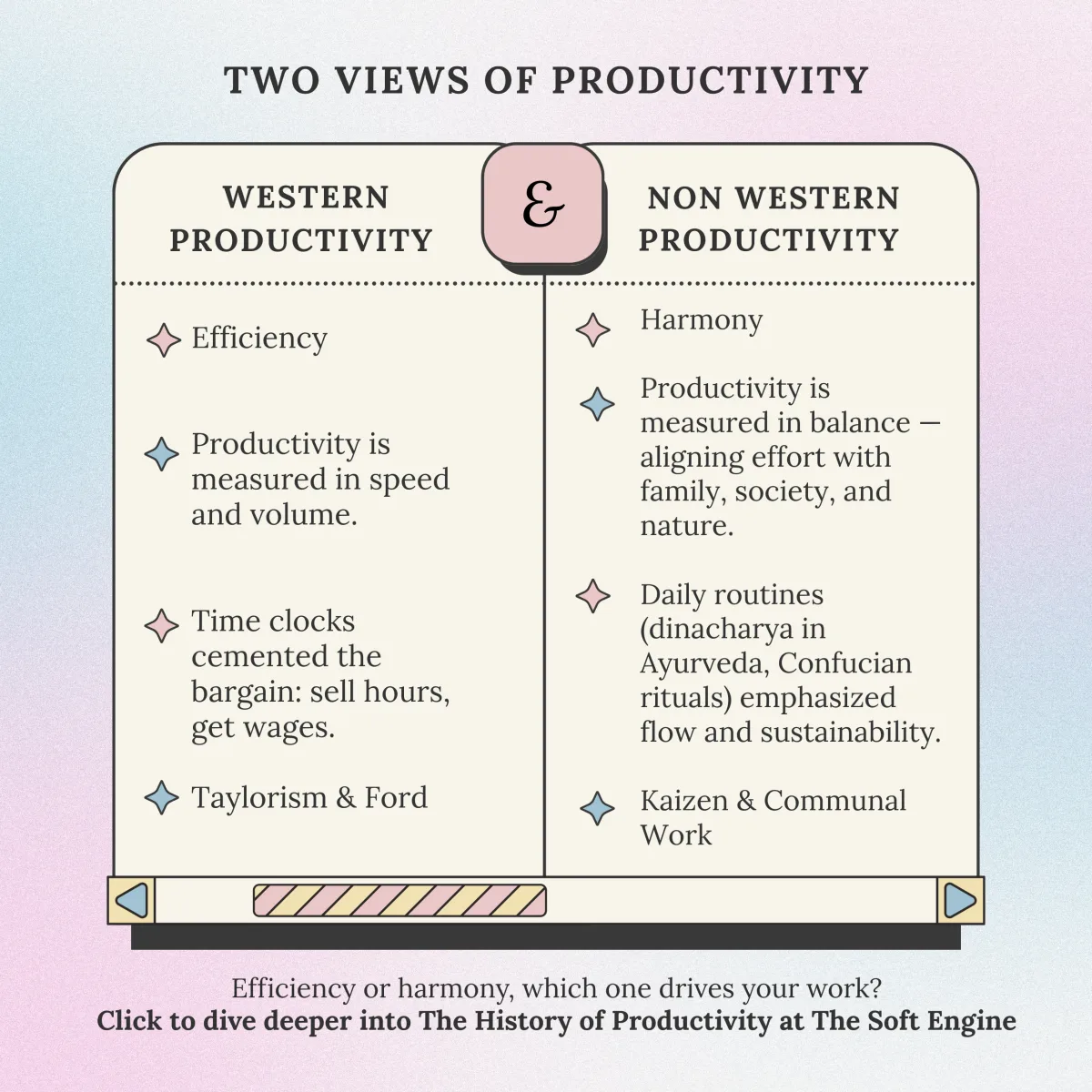

While tools optimized tasks, cultures developed value systems that optimized people.

Productivity wasn’t only measured in output, but in whether work aligned with moral, spiritual, or communal goals:

- China (Confucianism): Work and diligence were framed as expressions of virtue. A “productive” person was one who contributed to family duty and social harmony, not just to personal gain. This created shared expectations that motivated labor without the need for constant oversight.

- India (Ayurveda and Yoga): Ancient texts like the Charaka Samhita emphasized dinacharya (daily routine), aligning sleep, diet, and movement with natural rhythms. Productivity was framed as sustained energy management. Modern research on yoga supports this, showing potential benefits for stress reduction, sleep quality, and cognitive performance — although findings vary by population.

- Japan: During the Edo period, communal farming systems cultivated efficiency through cooperation. Later, these habits crystallized into kaizen (continuous improvement) and lean philosophy, focusing on small, steady refinements that avoided waste.

- Islamic Golden Age: In Baghdad’s House of Wisdom (8th–13th century), productivity meant intellectual output. Scholars translated Greek, Persian, and Indian texts, preserved knowledge, and produced original advances in mathematics, medicine, and astronomy. Productivity was measured not in widgets but in wisdom transmitted.

The common thread: non-Western traditions viewed productivity as a blend of capacity, balance, and contribution. It was less about maximizing output per hour and more about aligning human effort with purpose and sustainability.

The Industrial Revolution: Speed Over Craft

Steam power and moving assembly lines reorganized work around throughput.

Frederick Winslow Taylor argued that management should study tasks, set standards, and enforce the “one best way.”

The Ford assembly line (1913) turned work into timed, specialized motions — output exploded, prices fell, and mass prosperity rose, but autonomy and variety shrank.

Time clocks cemented the bargain: sell hours, get wages.

Here’s what all that looked like in context:

- 1776 – Steam Power Scales Work

James Watt’s improved steam engine fueled mills, mines, and railways. One machine could replace dozens of workers or animals, shifting productivity from muscle to machine.

- 1776 – The Pin Factory Example

In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith described a pin factory where 10 workers, each doing one small task, could produce 48,000 pins a day — versus just a few hundred if each worked alone. Specialization became the new engine of productivity.

- Late 1800s – Factories Multiply

Workshops gave way to large-scale factories. Instead of one artisan crafting a product, labor was split into repeatable steps. Efficiency soared, but workers became cogs in bigger machines.

- Early 1900s – Taylorism and Scientific Management

Frederick Winslow Taylor used stopwatches and time-motion studies to find the “one best way” to do every job. His ideas created modern efficiency metrics — and sparked debate about whether humans were being treated like machines.

- 1913 – Ford’s Moving Assembly Line

Henry Ford adapted the “disassembly lines” of meatpacking plants into car production. The results were dramatic: Model T assembly time dropped from 12 hours to 90 minutes. Cars got cheaper, wages doubled, but jobs grew monotonous.

- 1920s – Time Clocks Cement the Bargain

Workers began selling hours instead of output. Punching in and out became the measure of productivity, embedding a culture where presence mattered as much as performance.

Knowledge Work and the Drucker Era

By the mid-20th century, the economy began shifting away from smokestacks and assembly lines. Machines could already multiply physical output — the real bottleneck was thinking work: planning, analyzing, creating, deciding.

This was the era that Peter Drucker named the rise of the “knowledge worker.”

- 1959 – Landmarks of Tomorrow

Drucker introduced the idea that the most valuable employees weren’t factory hands but people who applied knowledge to solve problems. Engineers, managers, doctors, lawyers, teachers — their “tools” weren’t hammers or lathes, but information and expertise.

- 1960s–1970s – The Productivity Question

Drucker warned that while machines had boosted factory efficiency, organizations had no equivalent playbook for knowledge work. You couldn’t time tasks with a stopwatch the way Taylor did. The key, he argued, was designing work so that expertise produced impact, not just output.

Core Principles of Knowledge Productivity:

- Define the right tasks: Effectiveness mattered more than efficiency. Doing the wrong thing faster was still wasted effort.

- Align outcomes: Work needed to tie to results, not hours logged. A consultant’s value was in solving problems, not pages written.

- Autonomy with accountability: Knowledge workers needed freedom to think but also responsibility to deliver impact.

That’s all nice, but what did that look like? Let’s look at IBM:

By the 1960s, IBM was trying to make sense of scale. With engineers, managers, and sales teams scattered across continents, the real challenge wasn’t building faster machines; it was coordinating them.

It was making sure thousands of smart people weren’t reinventing the wheel in different offices.

IBM’s answer was to pioneer early corporate knowledge systems: standardized reporting, rigorous management training, and processes for sharing data across its global network.

It might seem obvious now, but that shift was huge.

Suddenly, the real limiter wasn’t how fast machines could stamp metal but rather how quickly ideas could move through an organization without stalling in red tape or vanishing in filing cabinets.

IBM and its peers proved that the real competitive edge came from coordination at scale: making thousands of specialists act like one organism.

It’s the same puzzle that haunts every workplace today, whether in a boardroom, a Slack channel, or a Zoom call.

There was a trade-off, of course. Knowledge work brought more autonomy, creativity, and intellectual fulfillment than factory labor. But it also created new bottlenecks — bureaucracy and information overload.

The Digital Revolution: Computers, Internet, and Email

If the Industrial Revolution gave us factories, the Digital Revolution gave us inboxes.

Think about the milestones:

- Computers shrank from room-sized mainframes to laptops that fit in backpacks.

- Networks connected offices, then continents.

- Email arrived and, within a generation, it became the heartbeat of the modern workforce

By 2014, Pew found that for “networked workers,” email was rated more important than even cell phones or social media.

And it’s easy to see why: it was searchable, asynchronous, and low-friction. Send a message in New York, get a reply in Tokyo before your coffee cools.

But here’s the paradox: the very tool that boosted communication throughput started to shred human throughput.

UC Irvine’s Gloria Mark has shown that constant email and notifications increase multitasking, elevate stress, and lead to more errors. One study found that when email was removed, people switched tasks less often and felt calmer.

In other words, email made work faster, but minds slower.

Future Forward: Where Productivity Is Headed Next

If history shows us anything, it’s that productivity keeps shifting shape. Once it was about farming yields, then factory output, then knowledge work, then digital speed.

Now, standing on the edge of the AI era, the question isn’t “How do we do more?” It’s “How do we do better?”

Three big currents are pulling us forward:

- Redesigning the workweek. Trials of four-day and reduced-hour schedules in the UK, Iceland, and elsewhere suggest that shorter weeks often preserve or even raise it, while cutting stress and turnover. Productivity, in other words, may become less about hours logged and more about energy preserved.

- AI as a co-pilot, not a boss. AI will handle the boilerplate and the busywork, while people focus on judgment, creativity, and relationships — the things that can’t be scripted.

- Sustainable productivity. After decades of burnout, the next frontier is balance. The most competitive organizations won’t be the ones that run people ragged. They’ll be the ones who design systems where people can produce their best work and still have lives worth living.

The pattern is familiar: every era of productivity redefines what counts as “enough.”

The next era won’t reward those who simply work faster. It will reward those who can combine focus, technology, and humanity into a system that actually lasts.

Final Thoughts on The History Of Productivity

From clay tablets to cloud servers, from sundials to Slack — the history of productivity is really the history of how humans try to wrestle chaos into order.

Each era gave us new tools, but also new tensions: efficiency vs. meaning, speed vs. sustainability, connection vs. overload.

Now, as AI redraws the map again, the challenge isn’t just to work faster. It’s to decide what “productive” should mean in a world where output is infinite but attention is not.

Maybe the lesson from history is this: productivity has never only been about getting more done. It’s about building systems (technical and human) that let us create, contribute, and still have enough energy to live fully outside the spreadsheet.

Curious about your starting point and how productive you are? Try this productivity assessment to figure out your baseline.